The Significance of 1,100 Acres Opening to Shellfishing in New Bedford Outer Harbor

by Dr. Joe Costa

First posted in March 2009

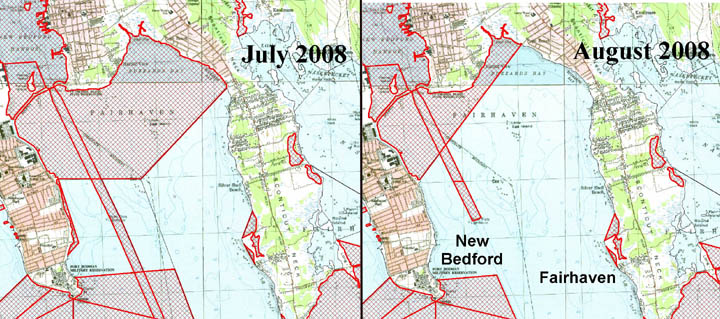

In August 2008, the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries did something rather profound. They opened more than 1,100 acres (see note 1) of Buzzards Bay to shellfishing, including some areas closed to shellfishing for more than 40 years. The newly opened shellfish resource areas were in outer New Bedford Harbor, and stretched from the middle of Clarks Point in New Bedford, to upper Sconticut Neck in Fairhaven (see illustration). The newly opened areas in Fairhaven are both productive and popular, and as of February 2009, the Town of Fairhaven is considering adopting some additional regulations to regulate shellfish harvesting in their newly opened areas (read this Southcoasttoday.com article: Fairhaven considers more curbs on dredge shellfishing).

What is particularly significant about this action was that it further illustrated the continued water quality benefits of local compliance with the 1987 Clean Water Act. It also highlighted the continued successes of the City of New Bedford and the neighboring Towns of Fairhaven, Dartmouth, and Acushnet to control both point and non-point sources of pollution, as well as the state Division of Marine Fisheries’ efforts and commitment to reevaluate contamination and health risks from municipal actions to eliminate pollution sources. The state’s actions in 2008 to reopen these long closed shellfish beds is one of the most recent outcomes of state and local actions over the past 20 years to better manage and treat wastewater and stormwater discharges, and improve water quality around the City of New Bedford.

Map of shellfish bed closures in July 2008 (left, red cross-hatched areas are closed to shellfishing) compared to closures in August 2008 (right).

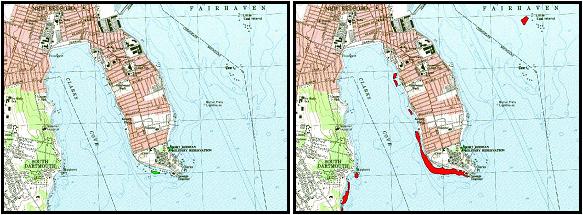

Status of CSOs in New Bedford as of June 2009.

The Beginning of the Turn-around

Dramatic improvements began occurring around the City of New Bedford beginning in the early 1990s. First, the city began an ambitious program to repair failed combined sewer overflows (CSOs). CSOs are sewage-stormwater overflow pipes found in older cities. In these cities, stormwater pipes were typically connected to sewer pipes for a combined discharge of sewage and stormwater during rainstorms. However, during heavy rains, the sewer system cannot handle all stormwater flow, so pipes are needed to divert the flow out of the systems (otherwise sewer manhole covers would be blown out of place by gushing sewage-laden waters).

These CSO pipes are supposed to discharge only during heavy rains, but in the early 1990s, many dumped raw sewage into coastal waters even in dry weather because they had not been maintained and were filled with sediments.

To address this program, the city began an ambitious program to improve their wastewater system. By 1992, the city had eliminated dry weather CSO discharges from Clarks Cove on the west side of Clarks Point (through at least 1996, two continuous discharges remained in the outer harbor, and two discharges remained in the inner harbor; see Appendix D of the City’s 2008 wastewater permit). At about the same time, the Town of Dartmouth also began reducing and treating stormwater discharges to its portion of Clarks Cove. These efforts, together with a rigorous testing and evaluation program conducted by the Division of Marine Fisheries (partly paid with Buzzards Bay NEP funds), resulted 800 acres of Clarks Cove being reopened to shellfishing in 1992 for the first time in nearly eighty years. (The area actually became a rainfall conditional closure: the area was closed after two tenths of an inch of rain until testing showed water quality was again good.) This reopening of shellfish beds in Clarks Cove in 1992 resulted 1.3 million pounds of quahogs coming to market in 1993, worth $2-3 millions in economic value to the region.

The next great improvement to water quality occurred in 1996. At that time, the City of New Bedford completed construction of its new secondary-level treatment wastewater facility. Prior to this date, the City discharged primary-treated or even raw sewage. A lawsuit initiated by the Conservation Law Foundation resulted in a court-ordered upgrade of the city’s wastewater facility in the 1980s, and by 1996, the new facility was completed. The construction of the new facility also enabled the elimination of one discharge pipe within 200 feet from the tip of Clarks Point, and restricted flow to the main outfall pipe that discharges 2,000 feet south of the city’s southernmost extension into Buzzards Bay. After the completion of the wastewater plant in 1996, the city redoubled its efforts to reduce CSO discharges.

Why the Shellfish Resource Areas Were Opened in 2008?

In plain terms, the MA DMF opened the beds because water quality testing showed that during dry conditions, bacterial levels in the water were below closure standards for shellfish beds. They acted because both the City of New Bedford and Town of Fairhaven achieved important reductions in pollution discharges. The City of New Bedford continued the early efforts described above to reduce CSO discharges and by 2008, nearly half the CSOs discharging in 1990 had been eliminated. In fact, the BBNEP funded the elimination of one of these CSO discharges in 2007 that contributed to the 2008 shellfish bed opening (read this march 2008 letter to EPA from Sewer Department Superintendent Ronald Labelle).

At the same time, the Town of Fairhaven was eliminating illicit discharges (as part of their Phase II stormwater program), treating stormwater, and expanded its sewering to Sconticut Neck, the peninsula of land on the eastern side of outer New Bedford harbor. Like Fairhaven, New Bedford began also mapping stormwater networks and eliminating direct discharges to surface waters.

The Eelgrass Connection

With the elimination of the CSO dry weather discharges in New Bedford, and the upgrade of the wastewater plant, there was an appreciable reduction in nitrogen loading and turbid sediment discharges, and water quality in Clarks Cove and the outer harbor greatly improved in water clarity. Suddenly swimmers and shellfishermen saw something they had never seen in New Bedford waters. Eelgrass was making a tremendous comeback to an area of Buzzards Bay it had been absent for decades. In 1985, a tiny refuge bed covering 0.8 acres existed near the tip of Clarks Point. By 1996 eelgrass bed acreage to the outer limits of Clarks Cove exceeded 27 acres, covering large portions of the shallow areas around the cove where eelgrass once grew five decades ago.

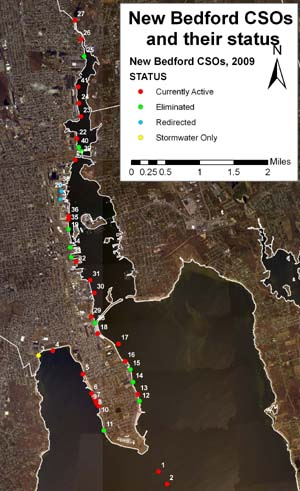

Comparison between mid-1980s eelgrass cover (left, note small green shaded area on the southwest corner of Clarks Point) and a 1996 survey of eelgrass (red shaded areas) showing a dramatic increase in eelgrass cover around Clarks Point New Bedford area. (The central areas of Clarks Cove are too deep for the growth of eelgrass.) Go to our historical eelgrass distribution page for more information.

The Big Picture

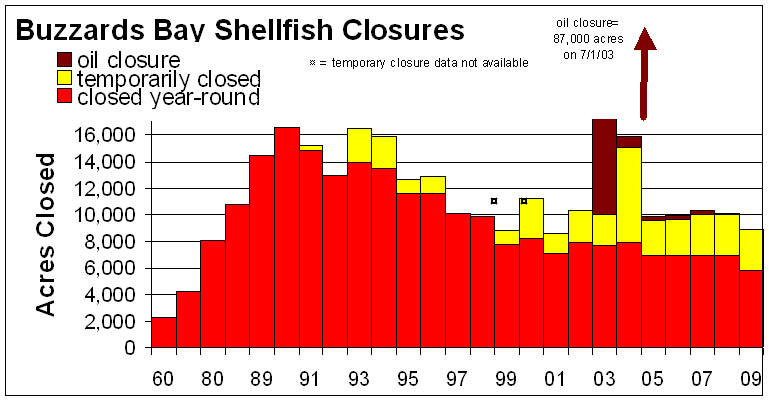

The opening of 1100 acres of shellfish habitat is important for other reasons as well. The opening of permanently closed areas has slowed around Buzzards Bay because of increased discharges from new development, and because many of the “low hanging fruit” of environmental restoration projects seemed to have been picked. The Buzzards Bay NEP tracks the status of shellfish conditions in Buzzards Bay as of July 1. With the August 2008 openings, the graph for July 1, 2009 is expected to look like the one below.

Projected shellfish bed closure status for July 1, 2009, based on the August 2008 shellfish bed openings in New Bedford and Fairhaven.

These reductions in nitrogen, bacteria, and particulate matter to Clarks Cove and the outer harbor parallel ongoing efforts to clean up the PCB Superfund site in the upper harbor and efforts to restore wetlands in the Acushnet River watershed. It reflects new attitudes by local government officials in protecting the environment as a priority, and a new attitudes by state and federal granting agencies to recognize the immensity of the challenge facing these communities yet still funding projects despite the long return time on these public investments.

A Lot More Work Needed

While these are all positive events, there is still much work needed in the waters around Dartmouth, New Bedford, and Fairhaven, and municipal officials in these communities recognize that. The Superfund site cleanup continues, and while other hazardous waste sites have been cleaned up, others remain. However, a general sense of optimism has stirred among residents and municipal officials that cleaning up pollution can really make a difference. As a sign of that commitment, in April 2009, the New Bedford City Council approved the expenditure of $19.3 million to fund the removal of nearly 6,000 cubic yards of PCB-contaminated grit from the city’s primary sewer pipe. The effort will not only remove a source of chronic toxic contamination to the bay, but it will increase the storage capacity of the wastewater system, further reducing CSO discharges (read the Southcoasttoday.com article: $19.3M OK’d for sewer clean-out in New Bedford).

Notes

Note 1: Newspaper articles state only 750 acres were opened, but these appear to be only areas opened in Fairhaven, and did not include all opened areas in New Bedford.

Related Links and Newspaper Articles

March 5, 2005 Standard Times article:$2.97 million is low bid for Acushnet sewer project

July 31, 2008 Standard Times article:Cleanup efforts pay off with expected opening of Sconticut Neck shellfish beds

August 3, 2008 Standard Times article:Cleanup of two sites is good news

August 3, 2008 Standard Times article:Fairhaven considers more curbs on dredge shellfishing

Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.