Historical Eelgrass Abundance: Apponagansett Bay

Note: The data and maps on this page will be included in a forthcoming report summarizing changes in eelgrass distribution in Buzzards Bay. The information is posted here to facilitate review of the information, but the data should be considered to be in draft form and subject to change.

On some nautical charts of the period 1890 to 1930 (prior to the wasting disease), in certain shallow bays where eelgrass is a particularly dominant feature, eelgrass is indicated by “grass” or “grs.” The figure above shows a portion of a National Ocean Survey Nautical chart from 1899 for Buzzards Bay, that clearly indicates eelgrass in Apponagansett Bay both near the mouth, and at the uppermost portion of the bay. Compare this map to the 1900 chart below.

Similar to the 1899 chart above, the figure above shows a portion of a National Ocean Survey Nautical chart from 1900 for New Bedford Harbor and approaches, that includes a portion of Apponagansett Bay, and indications of eelgrass.

Summary

For this assessment, only eelgrass habitat in inner Apponagansett Bay, the area north of the Apponagansett Bay Bridge, was evaluated. This embayment is broad, shallow, and protected, with bottom sediments in central areas composed of silts and muds. The dark muddy bottom of the inner bay is noted both in field reports, nautical charts (early charts note “STK” for sticky), and is evident in aerial photographs. These fine sediments are also easily resuspended on windy days and by boat traffic. Aerial photographs taken on windy days or after days of heavy rains are not interpretable for eelgrass mapping.

The Apponagansett bay watershed is small compared to the adjacent Slocums River and Acushnet River watersheds, but the watershed does include a portion of New Bedford. Much of the north and west portion of the Apponagansett Bay watershed remained farmland through the 1940s or later. The aerial photographic record show large numbers of homes built or expanded upon during the 1960s through 1990s. Most homes in the watershed were not sewered until the 1970s, and 1980s (the first were in Padanaram Village), and some much later.

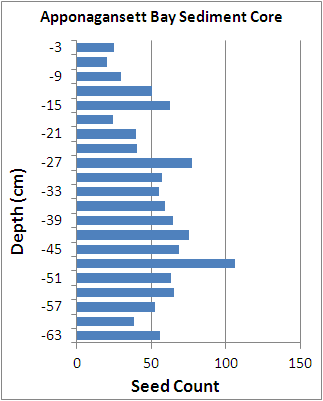

Nautical charts prior to the 1931-1932 eelgrass wasting disease, and a sediment core taken by Costa suggest that eelgrass once dominated Apponagansett Bay north of the bridge. No eelgrass was found in the inner harbor by Costa during field visits in 1984 and 1985, although the sediment core and local anecdotal information suggested some patches of eelgrass were present perhaps as late as the 1960s or 1970s. Eelgrass was not observed in the inner Apponagansett Bay by DEP in 1995, nor has eelgrass ever been mapped or reported in the inner harbor south of Little Island (in the conditional shellfish area) in decades (Harbormaster Steve Melo, pers. comm.).

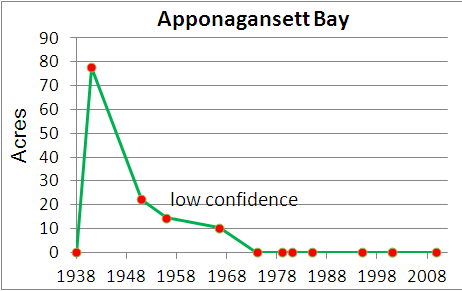

Estimated changes in eelgrass cover in Apponagansett Bay. More than most Buzzards Bay embayments, the interpretation of eelgrass in Apponagansett Bay is confounded by the long term abundance of drift algae in the bay, a likely symptom of more than half a century of eutrophication. Because of these confounding factors, the confidence level for eelgrass bed identification is low for photographs of the 1950s through 1970s.

Costa (1988a) noted, “Some parts of the inner harbor are covered with a rich gelatinous ooze of mud and decaying algae that has been observed in other enriched embayments….” Notes from those surveys indicate there were large accumulations of the red algae Agardhiella and Gracilaria as well as sheets of the green alga Ulva (sea lettuce). This accumulated drift algae is another confounding factor when interpreting aerial photographs of Apponagansett Bay, and this drift algae now appears to have been present over a long portion of the aerial photographic record.

In this new analysis, the original aerial photographs used in the 1988 study were reevaluated with improved image contrast and better mapping and photo registration techniques. In addition, numerous more recent high resolution photographs and previously unevaluated historical photographs were interpreted and compared. Special attention was given to paired spring-summer recent aerial photographs, and features in the newest high resolution imagery was compared to features in the historical photographs. The new analysis presented here excludes certain previously questionable vegetation areas in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s photographs.

Based on this new analysis it now appears that most of the benthic vegetation features in the September 1966 and April 1971 aerial photographs, and all the features in the October 1981 aerial photograph previously reported in Costa 1988 as eelgrass, were more likely to be drift algae. Even the areas identified as possible eelgrass as presented here, including the possible eelgrass beds identified on 1951 aerial photographs by DEP (classified as low confidence in identification in the GIS data set), may include or be composed largely of drift algae. Anecdotal information and the 1985 sediment core reported by Costa suggested eelgrass was present in some abundance after the wasting disease. Such high densities of eelgrass seed coats in the sediments are possible only if eelgrass were present in the inner harbor after the wasting disease because of how eelgrass seeds are dispersed.

Among the historic aerial photographs, the highest apparent eelgrass cover is found in a winter 1941 aerial photograph. The photograph was taken before the widespread use of chemical fertilizers on farms, and the number of homes in the watershed was still relatively low. In other photographs of this period, accumulations of drift algae in harbors are not apparent, so the vegetation features shown in this photograph could plausibly be eelgrass. Analysis of the photographs could be improved through interviewing senior lifelong residents and shellfishermen on the bay.

Despite the uncertainties in the interpretation of pre-1970 photographs, it is clear that whatever eelgrass may have been present between the 1950s and 1980s, the beds were small and insignificant compared to the widespread eelgrass cover prior to the wasting disease. The apparent widespread loss of most eelgrass by the 1960s or earlier, or the failure of eelgrass to return to pre-wasting disease abundance is consistent with the historic patterns of development in the watershed.

Mooring Impacts

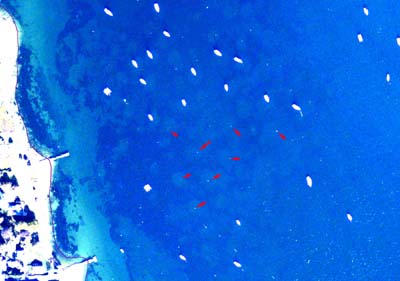

There are more than a thousand moorings today in inner and outer Apponagansett Bay. In the shallow waters north of the Apponagansett Bay bridge, water skiing was a popular pastime in previous decades. In Costa (1988a), both nutrient loading and increased turbidity from sediment resuspension by boats were identified as likely contributing causes to eelgrass declines in Apponagansett Bay. Based on aerial photographs of comparable periods, he noted a ten-fold increase in recreational boats between the 1940s and 1970s. Mooring scars are clearly evident in the outer harbor area in a late summer 2009 aerial photograph below, but the disturbed area in this photograph may be covered with algae, and not eelgrass.

Mooring chain scars in outer Apponagansett Bay observable in a fall 2009 aerial photograph (click photo to enlarge). The white dots indicated by the red arrows are mooring floats (representative examples) circled by lighter color sand showing the extent of mooring chain scour. The bottom vegetation in this area may be benthic attached and drift seaweeds, and not eelgrass. This NOAA photograph series is given as August 10 to October 21. Given the fall foliage apparent in the photograph (not shown), and the absence of many boats from their moorings (there were two hurricane near misses to SE Mass in August 2009 prompting early boat withdrawals), this photograph likely dates to late September to October 10. Image color was stretched, and contrast and brightness was enhanced.

Previous Summaries

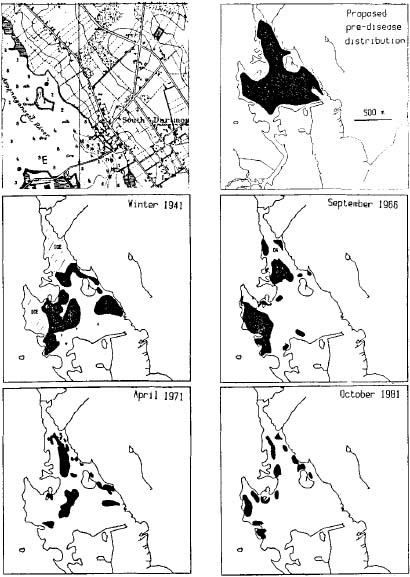

Costa (1988a+b) found no eelgrass in inner Apponagansett Bay during field visits in 1984 and 1985, but based on a sediment core in Apponagansett Bay, historical aerial photographs, and anecdotal information concluded, “eelgrass is abundant in the bay on nautical charts from the 19th century, eelgrass was destroyed in 1931-32, then showed recovery on aerial photographs during the 1950s and 60s, then disappeared again. (1988b),” and, “the most recent loss of eelgrass appears due to declining water quality from nutrient loading or increased turbidity from sediment resuspension by boats (Costa, 1988[a]).” There was uncertainty as to the identity of the vegetation in the 1981 photograph at the time, and Costa noted “Some vegetation appears along the banks at the head of the Bay in the 1981 photograph, but it was assumed to be largely composed of drift algae or Ruppia [widgeon grass].”

Based on the analysis of additional recent and historical aerial photographs, and a more detailed analysis of high resolution scans of the original study photographs, in this report it is concluded that all the vegetation in the October 1981 panel below, and possibly most of vegetation in the September 1966 and April 1971 panels, is in fact drift algae.

Data for the sediment core from Apponagansett Bay in Costa 1988a is shown below. It was taken 130 meters west of Little Island. Although eelgrass apparently disappeared from all of inner Apponagansett Bay when it was taken in 1985, it showed moderately high seed test counts in the top core segment (0-3 cm). This suggested the presence of eelgrass within the past decade or two, although perturbation of the sediments may blur the record here. No living eelgrass seeds were found in the top of the core, and occasionally one or two Ruppia seeds were observed in core segments. This sediment core had the highest seed density among the 5 sediment cores in the 1988 report.

Left: Estimated Historical changes of Apponagansett Bay eelgrass from Costa 1988b. Costa found no eelgrass in Apponagansett Bay in 1984 and 1985, but recorded these estimated historical changes in eelgrass coverage from aerial photographs and a sediment core. He noted “… eelgrass is abundant in the bay on nautical charts from the 19th century, eelgrass was destroyed in 1931-32, then showed recovery on aerial photographs during the 1950s and 60s, then disappeared again.” With respect to the vegetation indicated in the 1981 map panel above, there was some uncertainty, and he noted, “Some vegetation appears along the banks at the head of the Bay in the 1981 photograph, but it was assumed to be largely composed of drift algae or Ruppia.” There was uncertainty as to the identity of the vegetation in the 1981 photograph at the time, and based on additional and more detailed recent and historical aerial photographs, all the vegetation in the October 1981 panel above, and possibly most of vegetation in the April 1971 panel, is in fact drift algae.

Right: Sediment core data for Apponagansett Bay as reported in Costa, 1988.

Seasonality of Drift Algae in Apponagansett Bay

There is a strong seasonal pattern drift algae in inner Apponagansett Bay, with vegetation features more prominent in the fall, a pattern observable in both the spring-summer 2001 paired images, and the spring-fall 2009 images. In other embayments, such seasonality can be an indication of either annual eelgrass beds or increased growth of drift algae, but here the vegetation is drift algae. Annual eelgrass beds, tend to appear in very shallow waters, and tend to have a textured yellowish brown color (or lighter color in black and white photographs), whereas drift algae tends to have a dark flat appearance and are typically located in somewhat deeper areas and depressions. A striated pattern in a sheltered harbor is also typical of drift material. The dark circles at moorings (east side of photograph) are likely the result of drift algae accumulating in depressions caused by mooring chain scour.

Seasonal expansion of drift algae in West Cove between spring and fall 2009. See text for explanation.

Apponagansett Bay Historical Changes

No obvious eelgrass beds are evident in a December 1938 aerial photograph (below), the earliest aerial photograph available. However, this photograph has poor water transparency, and was taken just 6 years after the wasting diseases, and three months after the Hurricane of 1938 (September 21), so few conclusion can be drawn from this image. Elsewhere in Buzzards Bay, no obvious eelgrass beds were evident in the few aerial photographs obtained by Costa from the December 1938 survey for the 1988 eelgrass study, but in some Cape Cod embayments (like Waquoit Bay), eelgrass beds are distinct in the survey. One anecdotal report indicated eelgrass beds in outer Apponagansett Bay (off Bayview) were destroyed by the Hurricane of 1938 (H. Day, pers. comm.). It is unclear how much eelgrass had recovered by 1938 before the hurricane struck (eelgrass existed as just small patches in Buttermilk Bay about this time). Although it is difficult to discern in the 1938 photograph because the image was lightened and color stretched to better define submerged features in the bay, most of the upper watershed is dominated by farmland in this and photographs through the early 1950s.

The winter 1941 (probably January or February) photograph of Apponagansett Bay, although covered in ice in large areas, has some of the most convincing eelgrass bed features among any of the photographs. The sediment core was taken near Little Island, near the edge of this vegetation area. Subsequent photographs have features largely consistent with accumulated drift algae, although there are certain nearshore features that could be eelgrass beds, or a mix of eelgrass and drift algae, on the 1956 and 1966 photographs as indicated on the maps. Of note are the vegetation patches in the westernmost portion of West Cove in the 1966 color photograph that are brown colored. These features are consistent with heavily epiphitized eelgrass beds, but could also be accumulated algae in very shallow water. Analysis of the photographs could be improved through interviewing senior lifelong residents and shellfishermen on the bay, and by the analysis of new sediment cores.

An important feature observable in several photographs is the humic colored water plume arching toward the mouth of the bay from the Bayview village salt marsh. Water coloration, suspended sediments, and eutrophication likely all contributed to the apparent widespread loss of most eelgrass in Apponagansett Bay by the 1960s or earlier, or the failure of eelgrass to return to pre-wasting disease abundance.

Apparent absence of eelgrass in Apponagansett Bay on a 13 December 1938 aerial photograph. This photo was less than 3 months after the Hurricane of 1938, and 6 years after the wasting disease. Image quality is poor and water turbidity is high (note the swirling patterns of turbid water just north of the Apponagansett Bay Bridge). In the map above, there are some areas of the image that seem darker (marked “+?”, but the photograph is inconclusive as to whether there might be eelgrass in these areas). Click map to enlarge.

Apparent eelgrass Beds in a winter 1941 aerial photographs. Although large areas of the bay are obscured by ice, there is vegetation that has an appearance more consistent with eelgrass beds than drift algae. Compare this winter photograph to similar ice-covered images such as the February 1966 image of Megansett Harbor and the February 1966 image of Buttermilk Bay. Areas marked + are likely patchy areas of eelgrass.

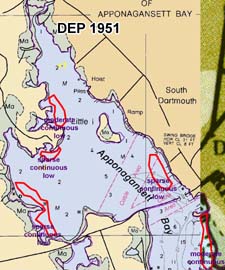

Possible eelgrass in Apponagansett Bay in 1951 as mapped by DEP. The bed at the south end of the inner harbor includes a portion of the deep channel near the bridge, an apparent misinterpretation. All these beds were assigned a “low” confidence of identification by DEP. Source photograph was not available. Click map to enlarge.

Possible Eelgrass in Apponagansett Bay in May 1956 as estimated by the BBNEP. Water transparency is poor, and benthic features are difficult to discern. The outlined areas have a slight stippled appearance and may be sparse eelgrass beds. These are in generally the same areas identified by DEP as possibly eelgrass, but this photograph is inconclusive, and the beds have a low confidence of being eelgrass. The area in the lower central bay marked A? may be algae, or some texturing from the mooring field. This area had eelgrass prior to the wasting disease, but the absence of eelgrass beds in shallow areas implies that this is not likely eelgrass. Click map to enlarge.

A May 1961 photograph of Apponagansett Bay. Water transparency is poor, and little information can be drawn from this image. Click map to enlarge.

An 11 April 1962 photograph showing little apparent vegetation in Apponagansett Bay. Water transparency is poor, and most benthic features have poor contrast with bottom sediments. These features are presumed to be algae, but the features marked “E?” have some similarity to eelgrass, but the confidence is low that these are eelgrass beds. Click map to enlarge.

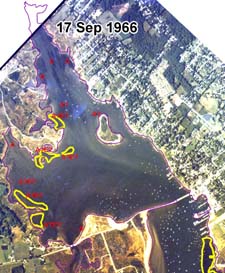

A 17 September 1966 photograph showing possible seagrass (eelgrass or widgeon grass) in inner Apponagansett Bay. The bed on the westernmost coast of West Cove is close to shore, and behind the small island at the north end of West Cove are brownish in color, which is consistent with heavily epiphitized eelgrass and widgeon grass bed. It is possible that these areas are accumulations of algae, or a mix of algae and grass. Note also the plume of water that is discolored by humic subtsances that leaves the Bayview salt marsh, and arches to the mouth of the bay. Click map to enlarge.

Aerial photograph of Apponagansett Bay of 8 October 1971. High turbidity of the water column (note swirling pattern of milky colored water; image enhanced) results in this image having little value for mapping eelgrass. National Weather Service records indicate that severe thunderstorms and high winds crossed all of Massachusetts on October 6, with local precipitation variable. The New Bedford weather station recorded 0.34 inches of rain on October 6 and 7.

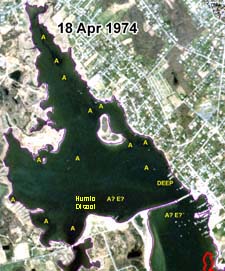

Aerial photograph of Apponagansett Bay of 18 April 1974. Although the image is of low resolution, patches of drift algae are clear at the head of Apponagansett Bay. The photograph is atypical in that sandy shoal at the south end of the bay appears covered with vegetation, but this apparent feature is partly an artifact of the fact that a plume of water leaving the marsh and flowing to the bay entrance is darkly discolored brown with humic material. Compare this photo to the 1979 image, which shows an the absence of vegetation there, and the apparent plumes of discolored water leaving the Bayview marsh on the 1966 and 1971 photographs.

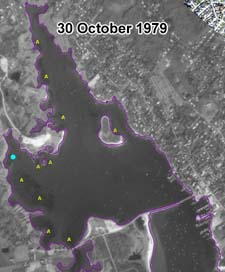

Apparent absence of eelgrass cover in a 30 October 1979 aerial photograph. The striated vegetation bands in the western cove (and some other areas) is an unusual pattern for eelgrass beds in protected embayments, and is characteristic of drift algae, which form winnows parallel to tidal currents. The vegetation pattern in West Cove is quite similar to the striated pattern illustrated in the fall 2009 aerial photograph. Note that all the vegetation in this photograph tends to be banked along the western shore of the bay. Click image to enlarge.

Apparent absence of eelgrass cover on a 10 October 1981. The vegetation indicated by question marks were omitted from the Costa 1988 report maps because a 1984 field visit indicated these areas were dominated by algae, and were presumed to be the same three years earlier when the aerial survey was made. Click image to enlarge. It is likely all vegetation patches in this image are drift alga.

DEP did not find eelgrass in inner Apponagansett Bay in its 1995 survey, here illustrated on a June 1994 aerial photograph. DEP only found algae at the four sites visited. Red arrows show apparent accumulations of drift algae visible in the 1994 aerial photograph. Note that drift algae tends to accumulate in deep areas in each part of the estuary, and the pattern of dense elongated accumulations in the north end of the bay is consistent with drift material. Compare this pattern to the apparent distribution of eelgrass beds in shallow areas close to shore in the 1979 photograph. Click image to enlarge.

This April 2001 aerial photograph shows an absence of eelgrass in inner Apponagansett Bay. Dark vegetation is characteristic of drift algae, which tends to drift and settle in deeper areas. There are two small areas in the central west port of the bay that have similarity to an eelgrass signature on aerial photographs, but the presence of eelgrass there is unlikely. Contrast the location of the drift algae in the west central portion of the bay in this photograph to the June 2001 aerial image. Click image to enlarge.

Absence of eelgrass DEP 2001 survey on original June 2001 source aerial photograph. Comments added to image are those of the BBNEP. The area identified as drift algae in the western cove shifted east and expanded from the April 2001 image. Click image to enlarge.

Absence of eelgrass in the MassGIS May 2009 aerial photograph. There are two vegetation features in the bay near the small island at the north end of West Cove that show some similarity to eelgrass vegetation. Contrast this photograph to the Fall 2009 photograph which shows considerable expansion of drift algae areas. Click image to enlarge.

Absence of eelgrass in a NOAA fall 2009 aerial photograph. The striated pattern of the features parallel to tidal flow and their dark coloration of are strongly characteristic of drift algae in a protected harbor. Compare West Cove in this photograph to the October 1979 black and white photograph. Click image to enlarge.