Herring Run Information for Buzzards Bay

Related document: 2002 Adamsville Pond Restoration

Herring Biology 101

Herring are small, streamlined, laterally compressed silvery fish in the family Clupeidae. They are plankton-feeding (planktivores), typically traveling in large schools. The more than 200 species in this family share several distinguishing characteristics such as a single dorsal fin, no lateral line, and a protruding, bulldog-like lower jaw. Unlike many other fish, herring have soft fins that lack spines.

Herring typically migrate thousands of miles as part of a feeding and mating cycle. While some herring lay their eggs at sea and are exclusively marine (e.g. the Atlantic herring and Atlantic menhaden), some species are anadromous, migrating up rivers to lay their eggs in streams and ponds, much like the Atlantic salmon and American shad (although both these fish lay their eggs exclusively in streams). These river herring of the northeast U.S. are the alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus) and blueback herring (Alosa aestivalis).

River herring spend most of their life in salt water and return to fresh water to spawn, usually between April and June in Buzzards Bay. Alewives typically return and spawn several weeks earlier than the bluebacks. In general, spawning is initiated for alewives when the water temperature reaches 51 F (10.6 C), and for bluebacks when the water temperature reaches 57 F (13.9 C). Alewives generally spawn in ponds and slow rivers, bluebacks spawn generally in streams. During spawning, the eggs settle and stick to gravel, stones, logs, or other objects. Unlike Pacific salmon, after spawning, herring typically survive and move back to the sea. Young fish typically return to the sea toward the end of summer or early fall, when they are about 1-1/2 to 2-1/2 inches long.

Juvenile herring schooling in one foot of water in Buzzards Bay, early October 2004. Juvenile bluefish (snapper blues) stalk in deeper water twenty feet away, waiting for the opportunity to feed on the herring. Photo credit: Dr. Joe Costa.

Like salmon, adults typically return to the same stream in which they were hatched. Consequently, after obstructions are removed from a river, or a fish ladder is installed, migrating herring must be physically transported to upstream ponds to restore the population, rather than wait for herring to accidentally discover the new habitat.

River herring are important to coastal and freshwater ecosystems of the Buzzards Bay watershed. Not only are these fish historically important as a fishery in Buzzards Bay, but adult and juvenile herring are also an important food species for many recreational fish (like striped bass and bluefish), whales, and coastal birds such as ospreys and the roseate tern (Sterna dougallii), a US endangered species whose largest colony in North America resides in Buzzards Bay.

Herring Declines

Throughout the twentieth century river herring populations in the Buzzards Bay watershed showed dramatic declines. These declines were believed to be caused by many factors including physical obstructions to migration, overfishing, poor water quality, or inadequate spawning habitat. Of these, physical constraints in the form of dams, obstructions associated with roadway construction (e.g. collapsing or obstructed culverts), failing anadromous fish bypass structures, and other obstructions were identified in the 1991 Buzzards Bay CCMP as among the greatest impediments to herring migration in Buzzards Bay herring runs.

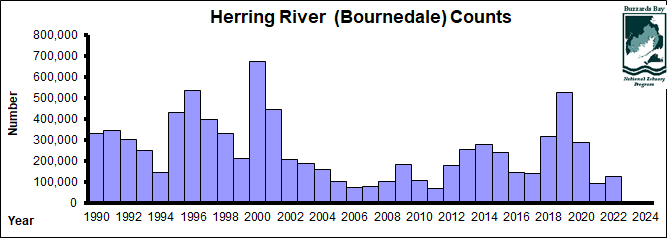

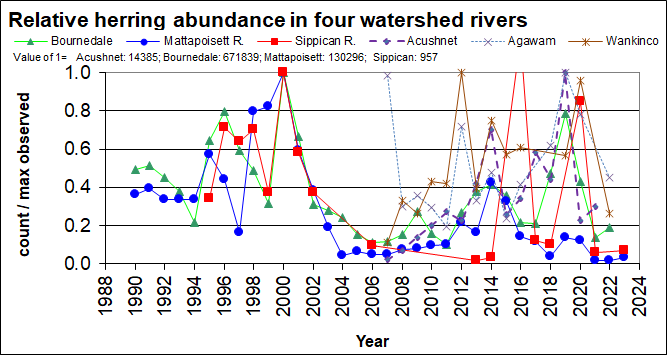

Because of these concerns, during the 1990s, and into the 21st century, the Buzzards Bay NEP provided funding and technical support to towns to help improve herring runs in the bay’s most productive river systems. The Buzzards Bay NEP’s efforts, together with more comprehensive contributions and leadership by the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF), and actions by local officials paid off. In the late 1990s, several area herring runs showed increasing return of river herring (see figures below.).

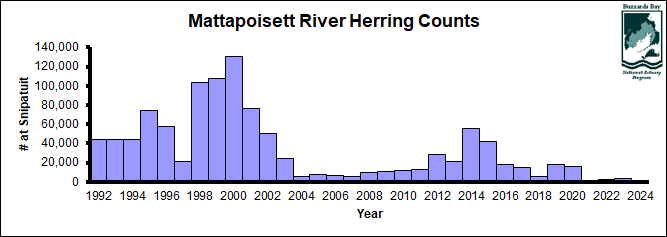

However, after 2000, river herring began to show new unprecedented and precipitous declines. These declines were observed not just in Buzzards Bay, but throughout the eastern seaboard of the US. Herring runs which might have once had hundreds of thousands of returning fish, now were reported to have declines of 90% or more of the population. These new declines appeared to be independent of improvements or declines in water quality, changes in habitat, or development patterns of each river herring watershed. When the long-term history of runs is examined, the trends are more dire. Important herring runs like the Mattapoisett River went from sustaining millions of fish in 1900, to hundreds of thousands of fish in 2000, to just 5000 to 8000 fish between 2004 and 2007.

The large-scale disappearance of river herring has generated considerable national debate about the causes. Factors often cited as contributing to this decline include loss and degradation of habitat, overfishing (including offshore bycatch from ocean herring fisheries), and increased predation due to recovering striped bass populations (NMFS 2007, Hass Castro 2006, Wilson, 2007). In 2006, the NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service designated both blueback herring and alewives as species of concern (NMFS, 2007).

To address alewife and blueback herring declines, Massachusetts implemented a three-year moratorium on the catch of herring beginning in December 2005 and ending December 31, 2008. By the end of 2007, bans on herring fishing were also enacted by Rhode Island, Connecticut, and North Carolina. In 2007, several fishing environmental groups asserted these actions would remain ineffective because overfishing by ocean midwater trawling was the primary cause of these herring declines. Because of the impacts to herring stocks, and presumed impacts to offshore ground fisheries, in December 2007, several environmental groups filed a lawsuit against the federal government to ban this trawling from certain ground fish areas. Since 2008, Massachusetts has renewed the herring catch moratorium, and it will continue at least through 2025. Collectively these efforts appeared to pay off, as herring counts showed increases between 2008 and 2014.

Herring Fishery

Prior to the herring fishery moratorium enacted in 2008 banning the taking of herring statewide, the herring fishery was regulated by fishing days allowed (the taking of river herring was prohibited on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays), and it was prohibited to catch river herring with any net other than hand-held dip nets. River herring were also subject to additional regulations that may have been imposed by the local community if they felt a certain run was threatened or impaired. Before the herring catch ban, smoked or kippered herring and egg roe (served for example in omelets) were local delicacies, but most fish captured were used as bait for recreational fisherman or for bait in lobster traps.

Town of Bourne Herring Regulations

Click this Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Herring Information Link for the latest information and updates.

Recent Trends

Currently five runs in Buzzards Bay have counters: the Mattapoisett River, Sippican River, Agawam River, Wankinco River by Tremont Nail, and the Acushnet River. Improvements to the Mattapoisett River passageways in the mid to late 1990s resulted in dramatic increases to the returning herring populations by 2003. However, in 2003-2006, returning herring numbers in Buzzards Bay runs (comparative figure below) were exceptionally low. Some speculated whether the drop off was related to the Bouchard No. 120 oil spill, which occurred just before the start of the herring run season. However, this drop-off was seen statewide and was believed to have been due to an exceptionally late and cold spring that year. There are also strong correlations between temperature and precipitation as described in this report.

Data courtesy of Alewives Anonymous.

Data courtesy of Massachusetts DMF.

Buzzards Bay Watershed Runs

Mattapoisett River

The Mattapoisett River herring run is the largest run in the watershed and has been the subject of the most restoration efforts. In fact, in the 1990s, the Buzzards Bay NEP helped fund the Mattapoisett River dam repair at Rt. 6, and repairs to the ladder and sluiceway at Snipatuit Pond. This work was highlighted in a 1998 Mattapoisett River Herring Run fact sheet. Counts improved in 2001, followed by a collapse by 2004, a new peak abundance in 2014, but only 40% of the 2000 highs, followed by a near complete collapse in 2021.

Herring Run map from MA DMF

Links and Reports

Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries herring and diadromous fisheries page

Pew Trust 2007 report: Empty Rivers: The Decline of River Herring

- TR-78: Chase, B.C., and C. Reusch. 2022. River Herring Spawning and Nursery Habitat Assessment: Mattapoisett River Watershed, 2013-2014.

- TR-77: Archer, A.F., and Chase, B.C. 2022. River Herring Spawning and Nursery Habitat Assessment.

- TR-80: Sheppard, J.J., C. Reusch, C. Rhodes, M. Gendron, and E. Perry. 2023. River Herring Spawning and Nursery Habitat Assessment: Acushnet River Watershed, 2019-2020.

- TR-56: Sheppard, J.J., S. Block, H.L. Becker, and D. Quinn. 2014. The Acushnet River restoration project: Restoring diadromous populations to a Superfund Site in Southeastern Massachusetts.

TR-18: Reback, K. E., P. D. Brady, K. D. McLauglin, and C. G. Milliken. 2004. A survey of anadromous fish passage in coastal Massachusetts: Part 4. Boston and North Coastal. In preparation. Boston Harbor | North Shore | Merrimack | General Recommendations, Index, Appendices - TR-17: Reback, K. E., P. D. Brady, K. D. McLauglin, and C. G. Milliken. 2004. A survey of anadromous fish passage in coastal Massachusetts: Part 3. South Coastal. South Coastal | General Recommendations, Index, Appendices

- TR-16: Reback, K. E., P. D. Brady, K. D. McLauglin, and C. G. Milliken. 2004. A survey of anadromous fish passage in coastal Massachusetts: Part 2. Cape Cod and the Island. Cape Cod | Martha’s Vineyard | Nantucket | General Recommendations, Index, Appendices

- TR-15: Reback, K. E., P. D. Brady, K. D. McLauglin, and C. G. Milliken. 2004. A survey of anadromous fish passage in coastal Massachusetts: Part 1. Southeastern Massachusetts. Taunton River Watershed | Buzzards Bay Drainage | General Recommendations, Index, Appendices

Reback. 1970. Final completion report anadromous fish project 6496

Herring Organizations

Alewives Anonymous (Rochester, Marion, Mattapoisett, MA group)

References Cited

NMFS 2007. Species of Concern: River herring (Alewife & Blueback herring) Alosa pseudoharengus and A. aestivalis. NOAA species of Concern NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Fact Sheet 11/2/2007

Haas-Castro, R. 2006. Status of Fishery Resources off the Northeastern US: River Herring. NEFSC – Resource Evaluation and Assessment Division at https://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/sos/spsyn/af/herring/ (last accessed 1/28/08)

Wilson, J. 2007. Fish of Yesterday, Fish of Tomorrow. NC Wildlife Magazine October 2007, pp20-31.

Herring Alliance. 2007. Empty Rivers The Decline of River Herring and the Need to Reduce Mid-water Trawl Bycatch. October 2007 available at www.herringalliance.org/images/stories/Herring_Alliance_River_Herring_Report.pdf last accessed 11/06/19