Municipal Populations, Water Use, and Occupancy Statistics

Related pages: MEP Septic Loadings | Massachusetts Estuaries Project | Subwatershed Statistics | Citizen Monitoring Program | 1992 Nitrogen Action Plan | Eutrophication Index |

By Joe. Costa. Last update 8 March 2012. Please report errors or send comments about this page to Joe Costa.

No matter how watershed loading rates are modeled, because septic systems are typically a major source of nitrogen in most coastal embayments, and because loadings from septic systems are fundamentally related to the occupancy rates and periods of occupancy of the dwellings they serve, estimating occupancy and septic system use is a fundamental requirement of all nitrogen loading models. US census data are a valuable tool in this respect, particularly because US Census 2000 and 2010 data are available in GIS form, and occupancy rates can be calculated down to the block level, making the data highly suitable for subwatershed loading calculations. The downside of the US Census data is that it is a wintertime population estimate, which is particularly problematic for highly seasonal communities as are found on Cape Cod.

The Massachusetts Estuaries Project sought to overcome this issue by using municipal water use records. This approach solves the main problem of identifying seasonal or occasional use properties. At the same time, it has the potential to overestimate wastewater discharges in villages and neighborhoods where swimming pools and automatic lawn sprinklers are more common. On this page we illustrate some important aspects of Census and water use data for the purpose of estimating wastewater discharges.

Population Seasonality and US Census Occupancy Rates

When evaluating water use records of properties in a watershed, it is important to compare this average water use of all properties (which may include year round, seasonal, and weekend use properties), to the US Census average occupancy rate of all properties (both vacant and occupied) in watershed, and not just the occupancy rate of all occupied properties. The table below illustrates the range of variability in overall occupancy rates and seasonal population shifts in the Buzzards Bay watershed and two seasonal communities on Cape Cod, for both the 2000 and 2010 census occupancy data. For example, in 2000 the town of Acushnet had 97.5% of all units occupied during the winter, and the town estimates a negligible increase in summer population. It annual occupancy rate (among all properties) is 2.6 persons per unit. In contrast, the outer Cape Cod Town of Chatham has a year round population of only 6,600 but that population swells to over 29,000 in the summer. Despite this remarkable shift of a town wide average occupancy of 0.98 persons per unit in the winter (less than half of all units are occupied in the winter), to 4.3 persons per unit in the summer, the annual average town-wide occupancy rate is still only 2.3 persons per unit (annual mean = 1/4 summer occupancy+ 3/4 winter occupancy, assuming a consistent June, July, and August population). Notice however, that whether a community has a large increase in summer population or not, the number of persons per occupied unit falls in a narrower range. Alternate approaches could employ data for Cape Cod using the 2008 Survey of Cape Cod Second-Home Owners.

| Municipality | 2010 census population | 2010 Total Housing Units | 2010 occupied housing units | 2010 vacant housing | 2010 occup. rate, occup. Units | 2010 Occupancy Rate, All Units | Assumed summer pop. | Weighted annual occupancy, all units | 2008-2010 mean reported RCGPD |

| Acushnet | 10303 | 4118 | 3934 | 184 | 2.62 | 2.50 | 63.33 | ||

| Bourne | 19754 | 10805 | 7866 | 2939 | 2.51 | 1.83 | 40,000 | 2.30 | 57.67 |

| Carver | 15059 | 4600 | 4297 | 303 | 3.50 | 3.27 | nl** | ||

| Dartmouth | 34032 | 12435 | 11237 | 1198 | 3.03 | 2.74 | 61.67 | ||

| Fairhaven | 15873 | 7475 | 6672 | 803 | 2.38 | 2.12 | 57.33 | ||

| Fall River | 88857 | 42750 | 38457 | 4293 | 2.31 | 2.08 | 67.67 | ||

| Falmouth | 31531 | 21970 | 14069 | 7901 | 2.24 | 1.44 | 100,770 | 2.22 | 67.67 |

| Freetown | 8870 | 3317 | 3162 | 155 | 2.81 | 2.67 | 54.00 | ||

| Gosnold | 75 | 215 | 39 | 176 | 1.92 | 0.35 | nl** | ||

| Marion | 4907 | 2445 | 1896 | 549 | 2.59 | 2.01 | 69.33 | ||

| Mattapoisett | 6045 | 3262 | 2505 | 757 | 2.41 | 1.85 | 51.67 | ||

| Middleborough | 23116 | 9023 | 8468 | 555 | 2.73 | 2.56 | 60.33 | ||

| New Bedford | 95072 | 42933 | 38761 | 4172 | 2.45 | 2.21 | 55.33 | ||

| Plymouth | 56468 | 24800 | 21269 | 3531 | 2.65 | 2.28 | 76.67 | ||

| Rochester | 5232 | 1885 | 1813 | 72 | 2.89 | 2.78 | nl** | ||

| Wareham | 21822 | 12256 | 9098 | 3158 | 2.40 | 1.78 | 43,644 | 2.23 | 55.33 |

| Westport | 15532 | 7193 | 6154 | 1039 | 2.52 | 2.16 | nl** | ||

| Mashpee | 14006 | 9882 | 6118 | 3764 | 2.29 | 1.42 | 30,684 | 1.84 | 48.67 |

| Chatham | 6125 | 7343 | 3085 | 4258 | 1.99 | 0.83 | 30,000 | 1.65 | 55.00 |

| Weighted annual occupancy is based on assumed summer population continuous for 3 months. | |||||||||

Municipal Seasonal Water Use

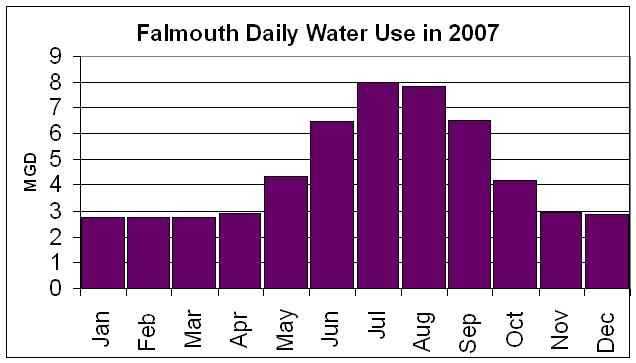

A general rule of thumb often used by planners and water managers is that per capita water use by residential units can increase by 50% in the summer because of lawn and garden irrigation and pool use. This is a confounding factor because the use of automatic lawn irrigation systems has increased in the past decade. Besides this increased water use during the summer for year round homes, some homes are occupied only in the summer, and summer populations in some Cape Cod towns may double or triple for a few months during the summer. The resulting trends in seasonal water use is illustrated by the graph of water use in Falmouth, as illustrated in the graph below.

For example, in the Town of Falmouth, the population served by municipal water shifts from 33,000 in the “winter” (October to May) to an estimated peak of 77,500 served in the summer (from Town of Falmouth 2008 annual report, this total is unlikely persist throughout the entire summer). The town reported an annual average annual daily flow of 2.461 MGD. Assuming a conservative 4 month/8 month split in the summer/winter populations (annual weighted population would be 47,833), this equals an average of 51.4 gallons per person per day (including summer irrigation use). This value on one hand is an overestimate because the town does not break out commercial and industrial water uses, and on the other is an underestimate because peak population is not maintained for four months.

A better understanding of these trends can be discerned in a plot of the town’s monthly water use. As shown below, water use in Falmouth is remarkably steady between November and April, which probably reflects the year round population use and other sources. Average monthly flow during this period is 2.83 MGD, whereas during the peak summer months of July and August, when population served may reach 77,500, and water irrigation is peaking, more than doubling to 7.22 MGD. If these periods reflected the populations of 33,000 and 77,500 respectively, this would translate to 85.8 and 93.1 gallons per capita served. The per capita increase during the summer (about 10%) is likely the result of increased outdoor uses. The gallons per day usages are not actually estimates of residential water use because commercial (restaurants), educational (schools), and industrial water users are separated in this analysis.

For comparison to these numbers, each town water depart or district does annually report residential gallons per capita per day (RGCPD) to DEP (total residential water use divided by estimated population served, see DEP RGCPD reports). In 2006, the Town of Falmouth estimated RGPCD at 74, with 4% of the water service unaccounted for. DEP and municipalities have been revising and improving their methodology as outlined on the DEP website, and water use in drought years can be higher. In 2009, Falmouth reported RDCPD was only 61 gpd. As noted on the DEP RGCPD website, “Higher RGPCD values may indicate that residents of the system use substantial water for outdoor use, notably lawn watering. Lower RGPCD values may indicate that a community controls outdoor water use or that the community is densely settled with small lawn areas (for example, cities).” The RGCPD has its own set of biases in that it is typically calculated using the US Census occupancy rate of occupied units applied to all accounts.

MEP approach to Onsite Wastewater (Septic System) Calculations

When water use data is available from a municipal water department, they may take the average of several years of data for each property in the watershed being studied. The MEP assumes that, on an average annual basis, and as an average of many houses in a watershed, 90% of residential water use goes into the septic system, and 10% is non-wastewater use, being used for swimming pools, lawn and garden watering, and other outdoor uses. This assumption is actually applied to all non-residential and commercial properties as well that are presumed to have a septic system. They then multiply this presumed septic discharge by an septic system discharge of 26.25 mg per liter (ppm) for a conventional wastewater system.

While the loading calculation is sometimes arranged as described above in some MEP loading spreadsheets, more commonly the 90% coefficient is applied to the wastewater concentration. Thus MEP TMDL reports refer to a “wastewater loading coefficient” of 23.625 mg per liter (=26.25 x 0.90), which is applied to the entire property water use. In most TMDL reports, the authors write, “As a result, MEP staff has derived a combined term for an effective N Loading Coefficient (consumptive use multiplied by N concentration) of 23.63, to convert water (per volume) to nitrogen load (N mass).” This means they took the total billed water use (“consumptive water use”), and multiplied it times 23.625 ppm to calculate the estimated total septic loading. Presumably, they take this approach to simplify calculations in the loading spreadsheet.

To evaluate the reasonableness of those estimates, the MEP may take census average occupancy adjusted for municipal estimates of summer occupancy, and multiply these average annual occupancies times 55 gallons per day per person for presumed wastewater discharge.

Real World Examples and Confounding Issues

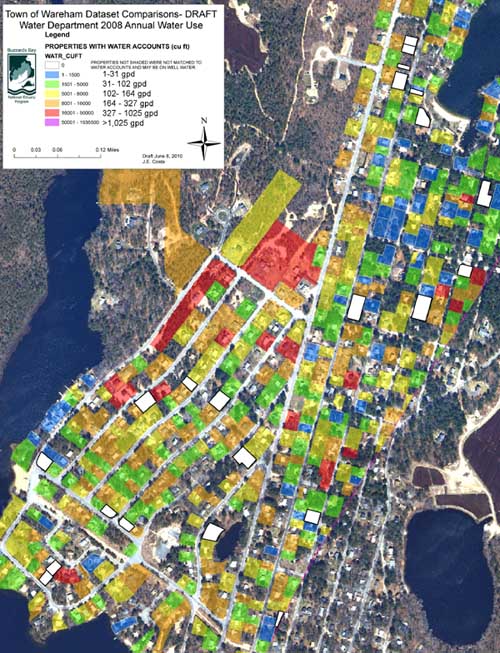

The Buzzards Bay NEP obtained water use data from the Town of Wareham to evaluate total water use in the Wareham River watershed. We found that some coastal villages, and some upper watershed villages like Shangri La, have highly seasonal or weekend-only populations which are reflected in the parcels with low water in the map below. Many of these properties had annualized average water use less than 30 gallons per day (gpd). In contrast to these low rates, many year round homes in the center of town had water use close to 180 gpd, a more typical residential water use rates with occupancy rates close to 3 persons per unit. Still, because the large number of homes in the Wareham River watershed that appear to be seasonal or weekend occasional use properties, the mean watershed water use was only 131 gpd. These values are discussed and incorporated into our Wareham River watershed nitrogen loading calculations.

Variable water use in Shangri La Wareham, MA. Click image to enlarge.

Of course, common sense and professional judgment must be used when incorporating water use data into loading spreadsheets. For example, in the Town of Wareham, one trailer park had a remarkably high average annual use of 287 gpd per unit. This was more than twice the average of units in other trailer parks in town. After consulting the water department, they informed us that the private water distribution system serving the 140 units was leaky, and a large amount of water serving the trailers was presumed lost to the ground. For a nitrogen loading analysis, for this development it would be best to apply an average water use found in other trailer parks in town.

In some other watersheds, the assumption that only 10% of water consumption is used for outdoor uses may considerably underestimate actual non-wastewater flows. In the Quissett Harbor, Falmouth watershed we discovered that many properties had 5 to 10 times the water use of an average home in town. While some of these homes were large, they did not necessarily have 5 to 10 times the number of people in them. Rather a review of aerial photographs showed that many of these homes had extensive landscapes, swimming pools, and docks. These discrepancies can be seen when examining the average annualized daily water use among properties with and without pools or docks as shown in the table below (the two properties with both a pool and a dock averaged over 1000 gpd water use).

| Table 1. SFH property water use in the Quissett Harbor watershed with and without pools, and with and without docks. Both differences are highly significant | |||

| status | number | mean gpd | std dev |

| no pool | 105 | 182 | 195 |

| with pool | 7 | 721 | 461 |

| no dock | 103 | 192 | 227 |

| with dock | 9 | 493 | 379 |

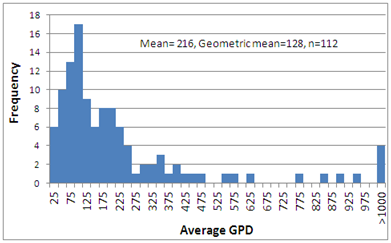

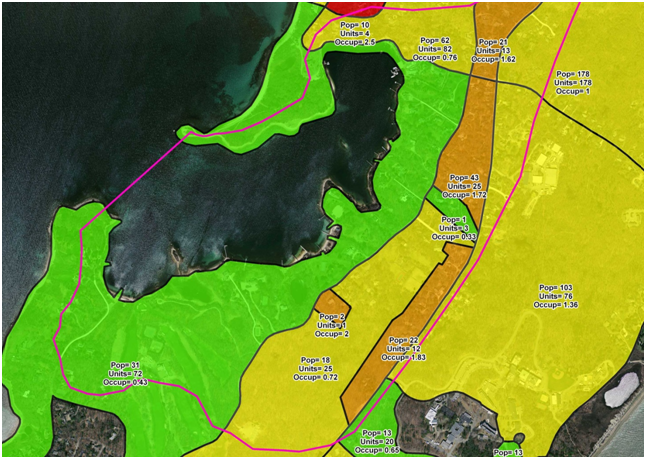

To best understand water use in this watershed, we can look at the frequency of annualized average water use among all single family homes in the watershed, which is illustrated by the chart below. Note that many homes have only 50 to 75 gpd annualized average water use. To put these values into perspective, an average single-family may use 170 gpd. If this same home is used only for three months a year at this rate, it would have an annual average water use of only 45 gpd [(3 x 170 + 9 x 0)/12]. We know many of these homes are not year round residences because the 2010 US Census shows that the areas around Quissett Harbor have exceptionally low occupancy rates (less than 0.5 occupancy, population divided by total units, see map below).

As shown on the chart, mean water use among all single-family in the Quisset Harbor watershed is an unusually high 216 gpd, with the average being obviously skewed by a few high water users. The geometric mean, or the central tendency of the data, however, is only 128 gpd. It is this lower mean that more likely represents average water use discharged to septic systems, and this value could be applied to all residences. This data set also illustrates the point that low water use is probably an excellent indicator of seasonal or low occupancy. High water use, on the other hand, could indicate either high occupancy (and wastewater flows), or large outdoor water use for some properties.

Frequency of water use for single family homes (assessors use code 1010 and 1011 only) in the Quissett Harbor watershed.

US Census 2010 blocks showing population, units, and census (winter) average occupancy. Data from US Census. Some small blocks were merged into larger blocks, and some boundaries were adjusted to more closely match road and parcel bounds.