Public Access to Buzzards Bay & Its Shore

Boat Ramps

Generally, boat ramps and launches that are owned by the State or Municipal government are open for use to any citizen of the Commonwealth. Municipalities, may however limit or preclude non-resident parking in municipal boat launch parking lots, or charge a fee for non-residents. Boat Ramps repaired or upgraded with state funds must always provide “equal access” to all Commonwealth residents. Go to our Buzzards Bay Boat Ramps and Launches page for more information.

Beaches

Beaches owned by State or Municipal government are open for use to any citizen of the Commonwealth. Municipalities, may however limit or preclude non-resident parking in beach parking lots, or charge fees to non-residents for parking (see the links to the LEYDON v. TOWN OF GREENWICH case and the Mongeau Bibliography for a list of national cases and precedents). Every town or state owned public beach in Massachusetts allows access by pedestrians to their beaches, irrespective of residency, although some may charge fees to all pedestrians (equal access). Owners of private beaches, including beach associations and clubs, can limit access by the public as allowed by law. Go to our Buzzards Bay Beach Information Page page for more information. Our Tidal Elevations page has some technical information on ownership of the tidal zone.

Resident-Only Beaches in Chilmark, MA

A visitor to our website pointed out that in Chilmark, MA, two town beaches (Lucy Vincent and Squibnocket) are restricted to residents only of the Town of Chilmark, or their guests or tenants. This is enforced even for foot traffic, and the town requires a beach access photo identification card that they issue for a $10 fee (see the Town of Chilmark website). This is the only municipality in the Commonwealth that issues resident-only beach access walk-on permit cards.

With various state and federal laws ensuring equal access to public lands and public facilities, it might seem improbable for any municipality in Massachusetts to attempt to limit public access (not just parking) to a public beach to only residents of that municipality. However, the situation in Chilmark is actually more complicated in that these two “town” beaches are really privately owned lands leased to the town (the town does actually own its own “public” beach elsewhere). According to the town, they assert that limiting access to residents-only is needed for them to ensure they are complying to the terms of the lease.

While a private property owners can certainly limit “public” access to their property to town residents only, this case is curious in that public resources (town personnel and time issuing and managing a permit program) are being expended on a private property managed by a public entity (with taxpayer dollars) that allows only selective access by the public. We have not seen a legal case addressing these particular circumstances.

Public Access to the Ocean and Private Property

Private property in Massachusetts is typically owned to the mean low water (MLW) mark, and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts owns lands below the MLW mark. However, Chapter 91 of the Massachusetts General Laws, preserves the public’s right to “fish, fowl, and navigate” waters of the Commonwealth, including lands in the intertidal zone (between the high and mean low water marks), even if it is privately owned. This law does not convey the right to cross private property or uplands to reach these areas. Some Chapter 91 licenses provide for public access to intertidal areas across intertidal areas.

For more information on the specifics of the Chapter 91 law, jurisdictional boundaries along the coast, and public access rights to tidal lands, visit these Commonwealth of Massachusetts websites:

Massachusetts Coastal Zone Management’s Page on Public Access to the Shoreline

Massachusetts Coastal Zone Management’s Public Access online locator

Massachusetts Coastal Zone Management publication on Public Access

Massachusetts Court System: Laws About Beach Rights

Massachusetts Attorney General’s FAQs of Public and Private Beach Access

Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection’s Chapter 91 Waterway Licensing Program

Massachusetts Public Access Board (DFWELE)

Public Lands, Bike Paths, Open Space, and Parks

Public lands, open space, bike paths, and parks owned by the State or municipal government are open for use to any citizen of the Commonwealth. Municipalities, may however limit or preclude non-resident parking in certain municipal parking lots (typically only beach parking lots).

Fairhaven, MA Phoenix Bike Trail

Mattapoisett, MA Trail Maps, Bike Path

Mass Audubon Wareham, MA Great Neck Trail

Massachusetts Myles Standish Forest Camping and Trail information

Lloyd Center (Dartmouth, MA) Trail Information

Shining Sea Bikepath, Falmouth, MA

Cape Cod Canal Bikepath, Bourne, MA

This figure, taken from a NOAA website, is technically incorrect because property ownership in Massachusetts extends to the Mean Low Water mark, not the mean lower low water (MLLW) mark.

Important Legal Cases

Can a town make a public beach, park, or other public areas limited to residents, even if you are on foot? The answer to this is complicated. Citizens have rights of access preserved by the common law “Public Trust Doctrine” and “Public Forum” rights preserved by the First Amendment to the US Constitution. Access via the Public Trust Doctrine, can be balanced by resource protection concerns. Thus, the Connecticut Supreme Court struck down a town’s resident-only beach access law, but the Washington state Supreme Court upheld a county ordinance that prevented the use of Jet-Skis in certain areas. The Connecticut case and the annotated bibliography of legal cases are worth reading:

LEYDON v. TOWN OF GREENWICH: Greenwich Connecticut Residents Only Beach law overturned on appeal, affirmed by Connecticut Supreme Court.

“[this appeal]…whether a municipality constitutionally may restrict access to a municipal park to its residents and their guests. We conclude that such a restriction is prohibited by the first amendment to the United States constitution and article first, Sections 4,2 5,3 and 14,4 of the Connecticut constitution.”

Public Beach Access: An Annotated Bibliography by Deborah Mongeau

New Bedford Standard Times 6/99 Article on lack of Buzzards Bay Access.

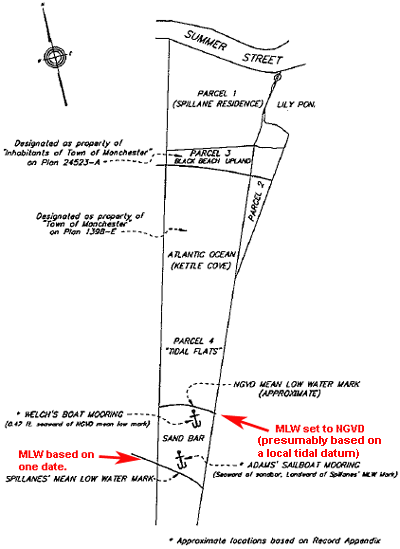

An interesting recent Lands Court case, that helps define ownership of intertidal areas, was upheld by an Appeals Court in 2010 (and affirmed in 2011 by the Massachusetts Supreme Court in its failure to take the case on an appeal). The case was a dispute in ownership between the town of Manchester-by-the-Sea and a private property owner, who removed some private moorings from tidal flats that he believed he owned. The case was decided based on a history of ownerships and land grants going back to colonial times, but the most important transferable outcome of the case was the fact that the court adopted a specific legal definition of the “Mean Low Water” for coastal property boundary cases. The judge concluded that the boundary line of MLW should be set to an elevation based on the North American Vertical Datum. The court wrote, “‘mean low water’ as established by the National Geodetic Vertical Datum (NGVD), is the appropriate standard for determining the low water mark”. Read more about the case in this Massachusetts Bureau of Municipal Finance Law article on Spillane v. Adams, 76 Mass. App. 378 (2010) (pdf), and at the Massachusetts Law Library beach Rights page. To understand the NGVD elevation, go to NOAA’s National Geodetic Survey: Frequently Asked Questions page, and the BBNEP’s Tidal Datums and Elevations page.

To those familiar with the application of elevation datums, this decision may at first seem innappropriate, because the NGVD does not “establish” MLW. NGVD-29 is an older elevation standard (adopted in 1929 based on the mean sea level at 26 stations around North America). It is a fixed reference point, not changing with rising sea levels. It was originally called the “Sea Level Datum of 1929” and “Mean Sea Level”, but in the 1970s it was recognized that these were misnomers, that the elevation was not even really mean sea level, so it was renamed the “National Geodetic Vertical Datum of 1929”. It does not equal mean sea level in Massachusetts (although in some areas it is close), and elevation is well above Mean Low Water. Moreover, the federal government has since migrated over to a new vertical datum for nautical charts, NAVD88, although many local engineering firms still prepare plans in NGVD29.

The judges in the case also called it the “NGVD mean low water datum”, but this is not the correct terminology. NGVD(29) is a datum (zero elevation), and it does not set the mean low water mark, which are based on tidal datums. Although the wording of some elements of the decision are imprecise from a technical perspective, the outcome of the case can be understood by a careful reading of the decision, and by reviewing references to the Land Court decision. Specifically, Mean Low Water (which is an elevation based on separate local tidal datums, a fact not explicitly mentioned in the decision), needs to be set to a particular land vertical elevation datum (in this case NGVD29) and applied to plans. This contrasts with demarcating a MLW boundary based on low tide observations on any particular day (as happened in this case). The map below shows the change in property bound set by the Land Court decision, and the table to the right shows the elevation of MLW based on the tidal datum near Manchester by the Sea as contained in a National Geodetic Survey database. As shown in that figure, MLW in the area of Manchester by the Sea is -4.31 ft NGVD29 and -5.12 ft NAVD88. Note that tidal datums (0 feet) is set to Mean Lower Low Water (MLLW), and in this case, MLW is 0.34 feet above the tidal datum.

For the purposes of local regulations, municipalities should require MLW be demarcated on site plans using National Geodetic Survey database tidal datums referenced against plan elevations (typically NGVD29 or NAVD88). For Chapter 91 Waterways Licenses, DEP requires plans to use either a NGVD or NAVD datum (as opposed to a relative benchmark), and the Chapter 91 regulations (310 CMR 09) define the mean low water mark as “the present mean low tide line, as established by the present arithmetic mean of water heights observed at low tide over a specific 19-year Metonic Cycle (the National Tidal Datum Epoch), and shall be determined using hydrographic survey data of the National Ocean Survey of the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Left: Diagram from Appeals Court decision showing demarcations of MLW considered. Right: National Geodetic Survey database tidal datums compared to NGVD for a station near Manchester by the Sea.