Wetland Delineation Training by the Buzzards Bay NEP

Related Pages: Eelgrass | Stormwater | 2013 Wetlands Action Plan | Acushnet Wetlands Case | Holly Woods Road Wetlands Case | Right to Appeal |

Profile: John Rockwell marks 23 years of wetland delineation training.

[Note: This page was first posted in 2011 before John retired from the Buzzards Bay NEP. Since then, John has continued to conduct wetland delineation training through MACC, which we sponsor, and we continue to update this page, including adding an updated versions of the guides at the bottom of this web page. If you want to attend a wetlands delineation course, please contact MACC.]

Since 1989, Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program Wetland Specialist, John Rockwell, has been training Conservation Commission members on how to delineate wetlands in cooperation with the Massachusetts Association of Conservation Commissions, MACC.

In addition to wetland delineation training with MACC, Mr. Rockwell has conducted delineation training for almost all the Conservation Commissions in the Buzzards Bay watershed, in addition to Conservation Agents, Boards of Health and Realtors.

Figure 1. Attendees at the 2009 Vegetation Training Workshop measure out the study plot. At contentious sites it is always wise to mark out the size of the plot so all parties can agree to what is in the observation plot. Photo by John Rockwell.

In 1983, the modern era of wetland delineation began in Massachusetts with the promulgation of wetland regulations, under the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act, M.G.L. 131 s. 40 (for a current copy of the law click Wetlands Protection Act ) that said that the edge of the bordering vegetated wetlands was determined by a plant community that was at least 50% wetland species. There was no definition of “plant community” or “wetland species” at the time, but over the next few years, some methods to delineate wetlands did develop.

By 1987, the forerunner of the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), the Department of Environmental Quality Engineering (DEQE), issued an Adjudicatory Hearing Final Decision, “In the Matter of Gail O’Connell and Brian Bierig,” that accepted both the Wetland Site Index (WSI) developed by Dr. Martin C. Michener, and the Relative Dominance By Layers (RDL) developed by Dr. Gary Sanford, as acceptable methods for determining the edge of a bordering vegetated wetlands.

In 1995, the DEP adopted the current DEP Delineation Policy concurrently with amending 310 CMR 10.00, the Wetland Regulations. In the policy, DEP established a clear methodology found in its delineation manual DEP Delineating Wetlands in Massachusetts Under the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act.

Figure 2. Notice the almost complete cover of cinnamon fern in the ground cover. Photo by John Rockwell taken at the BBNEP/MACC 2009 Vegetation workshop.

Delineation Theory:

Wetlands are created by wet conditions at or near the surface for sufficient time to create anaerobic condition in the upper part of the soil. We can’t see oxygen levels, so it’s lucky for us that wet conditions due to water near the surface (12 inches) for sufficient time make:

a. a wetland plant community

b. wetland soil morphologies

c. wetland plant adaptations

Figure 3. Soil sample from the BBNEP/MACC Advanced Delineation Training session. The sample contains both redox concentrations and depletions. Photo by John Rockwell.

Wetland identification is a four step process.

1. Plant identification;

2. Plant designation as a wetland indicator;

3. Determination of % wetland species and

4. Confirmation of wetland hydrology

The BBNEP has developed a four part series of workshops to train Conservation Commission members. The Vegetation workshop explains items #1-3 above, and the Soils section looks at #4. The Advanced workshops discuss special problems for those more familiar with the DEP Manual.

VEGETATION:

The Vegetation workshop focuses on the first three steps of the wetland identification process. You’ll need the following to get started:

The DEP delineation manual: Delineating Bordering Vegetated Wetlands in Massachusetts. This manual is the basis for delineating wetlands in Massachusetts. Download a copy and read it.

Since you can’t memorize all the things you need to in the DEP manual, we’ve made the updated 2024 Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program Pocket Guide to Delineating Wetlands that contains all the essential info and fits in your back pocket. Like all our pocket guides, print it out on a two-sided printer, 8.5 X 11 paper, landscape setting.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wetland “Plant List” is now maintained by the US Army Corps of Engineers. We’ve made a pocket size copy of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National List of Plant Species that Occur in Wetlands: Massachusetts 1988, which is cited as the official list in the Wetland Regulations at 310 CMR 10.55(2)c. Print it out on a two-sided printer, 8.5 x 11 paper, landscape setting.

When recording your data, the DEP data sheet found in Appendix G of the DEP manual is good, but the BBNEP Improved DEP Data Sheet is better.

You also might want to look at the 2014 Fall BBNEP/MACC Vegetation Workshop presentation that has all the lecture notes included.

Step 1: Plant Identification

Plant identification is done by a “key” that has artificially segmented a series of choices describing a plant. For example:

opposite vs. alternate leaves,

simple vs. compound leaves,

twigs hairy, or not so.

Unfortunately, there is no one book that will identify all plants well for the beginner. Magee’s book, Field Guide to Wetland Plants, does list the more common wetland plants. Plant guides are available from MACC and of course, online. They can cost anywhere from $4.00 to $25.00. Sometimes you can find them at used bookstores. Buy one you can use. Each key is designed by the author to make perfect sense. If it doesn’t work for you, get a different key.

You will need a field guide for the identification of:

Trees,

Shrubs,

Wild flowers,

Ferns, and

Grasses and grass-likes.

Concentrate on the more common wetland plants in your area. You don’t have to learn all the plants, just the wetland ones! Rely on the consultant to identify the species if you have a question, and then use the field guide to verify the ID. You can slide along the first year by just knowing the most common wetland plants in your area.

If you are in southeastern Massachusetts, you should learn the following wetland plants:

TREES

Red maple

Tupelo

Atlantic white cedar

Eastern hemlock

SHRUBS

Sweet pepperbush

Northern arrowwood

Swamp azalea

Highbush blueberry

FERNS

Sensitive fern

Cinnamon fern

Royal fern

GRASSES AND GRASS-LIKES

Phragmites australis

Soft rush

Canada rush

If you are in another part of the state, make your own list of most common plants – then learn them!

A Helpful Hint:

Maples,

Ashes,

Dogwoods, and

Caprifoliaceae. (Plants of the Caprifoliaceae family include Viburnums, honeysuckles, and elderberry.)

You can use the MAD-CAP phrase to narrow down what you’re looking for when using a tree or shrub key.

Remember that “Sedges have edges, Rushes are round“. While there are upland sedges and rushes, they should be considered guilty (of wetness) until proven innocent.

Web Resources

There are many good web sites to aid in plant identification. Here are a few with a brief description from the BBNEP staff:

The PLANTS Database https://plants.usda.gov/ The PLANTS Database provides standardized information about the vascular plants, mosses, liverworts, hornworts, and lichens of the U.S. and its territories. It has great photos.

New England Wildflower Society Simple Key: https://gobotany.nativeplanttrust.org/simple/. This is a great key to the plants of New England. Very Nice.

USDA Wetland Plant Search: https://plants.usda.gov/home/wetlandSearch. Generally speaking, in a non-botanical way, monocots are a class of non-woody flowering plants. This is a good key to be used for identification. Also find on the “plant keys” site keys to gymnosperms and grasses.

MEKA Homepage: https://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/meacham/meka/. This is a technical key for those who can identify plant families and understand botanical nomenclature.

Quick Guide to Common Ferns of New England: http://www.ct-botanical-society.org/Plants/gallery/12 The Quick Guide to Common ferns of New England was prepared by Connecticut Botanical Society member Arieh Tal. It is intended as a supplement to field guides or keys. It is organized as tables, allowing you to use multiple features for identification.

Solidago Dichotomous Key from Go Botany This is very good. Very handy.

Gallery of Connecticut Wildflowers www.ct-botanical-society.org/galleries/galleryindex.html. This collection of photos has the flowers of forbs and shrubs. You can sort by color, common name, or scientific name. This is at the Connecticut Botanical Society website.

Grass Identification: plants.usda.gov/plantkeys/massachusetts_grasses/MASSACHUSETTS_GRASSES.html. You need to know grass nomenclature to use this site. Better to get a copy of Lauren Brown’s Grasses. On the other hand it’s not that bad to use because there is a definition handy for every botanical term.

VTree, Virgina Tech, Department of Forest Resources and Environmental Conservation: http://dendro.cnre.vt.edu/dendrology/factsheets.cfm. This site is rich in information to ID trees. Has links to Android and iphone apps.

Trinomial Identification: https://directives.sc.egov.usda.gov/18534.wba

Has diagnostic info for nine species. Particularly useful for identifying the wetland version of American Beech, Fagus grandifolia. 16pp. color

Step 2: Plant designation as a wetland indicator

Remember, wetland delineation is an open book test. So just remember to bring your books. The following species have been designated wetland indicators and should be included; and are shown on the BBNEP improved DEP Data Sheet & page 6 of BBNEP Pocket Guide. You won’t have to memorize this.

1. All plants specifically listed in the Wetlands Protection Act. These include:

a. Red Maple

b. Tupelo

c. Canadian Hemlock

d. Sweet pepperbush

e. Sheep laurel

2. All Plants listed in the USFWS plant list that are given an OBL, FACW+, FACW, FACW-, FAC+, and FAC indicator status.

3. All plants in the genus Sphagnum.

4. Plants with Morphological adaptations to wet conditions. (see page 36 of the DEP Manual or page 27 of the BBNEP Pocket Guide as well as this site from Forest and Range for a discussion of plant morphology associated with wet conditions).

Explanation of OBL, FACW+, FACW, FACW-, FAC+, and FAC

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service has rated plants as to their percent occurrence in wetlands in Massachusetts.

The Massachusetts indicators reflect the range of estimated probabilities of a species occurring in wetlands versus non-wetlands. A positive (+) or negative (-) sign is used with the Facultative indicator categories (Facultative Wetland, Facultative, and Facultative Upland) to more specifically define the regional frequency of occurrence in wetlands The positive sign indicates a frequency, toward the higher end of the category (more frequently found in wetlands), and a negative sign indicates a frequency toward the lower end of the category, (less frequently found in wetlands), or the + and – designation was used to get agreement by the reviewers.

This list has been superseded for federal delineations only. See the notes at the USDA Plants webpage.

Indicator categories:

Obligate Wetland (OBL). Occur almost always (estimated probability, >99%) under natural conditions in wetlands.

Facultative Wetland (FACW). Usually occur in wetlands (estimated probability, 67%-99%). but occasionally, found in non-wetlands.

Facultative (FAC). Equally likely to occur in wetlands or non-wetlands (estimated probability, 34%-66%).

Facultative Upland (FACU). Usually occur in non-wetlands (estimated probability 67%-99%), but occasionally found in wetlands (estimated probability, 1%-33%).

Obligate Upland (UPL). Occur in wetlands in another region but occur almost always (estimated probability >99%) under natural conditions in non-wetlands in Massachusetts. If a species does not occur in wetlands in any region, it is not on the National List.

Step 3. Determination of % Wetland Species

How to Look at Vegetation – Communities and Growth Forms.

Vegetation describes the plant community, but how to describe the vegetation? The vegetation can be segmented into different vegetation layers. The layers agreed to for wetland delineation are:

Trees,

Saplings,

Shrubs,

Ground cover, and

Vines.

Not all layers may be present an in any particular plot. See page 3 of the BBNEP pocket guide to determine when plants belong in particular group.

Observation Plots

Look at the plants for each layer in the appropriate observation plats. Due to experience in “sampling” it has been determined that one does not have to observe all the plants along the wetland line. Observation plot sizes change with the vegetative layer being observed and the area being studied. Use the plot sizes and methods in the DEP Delineation Manual on page 11 or in the BBNEP pocket guide on page 3. When you start out this is hard to remember, so keep the BBNEP Wetland Delineation Pocket Guide handy.

Figure 4. The 2009 Vegetation Class identifies the vegetation in each layer. Photo by John Rockwell.

Percent Cover Estimation

Estimating the “amount” of a plant has become standardized and fairly easy to learn. Pick a range of cover and use the median of that range to record as present for that species. The standard ranges for estimating cover are on page 12 of the DEP Manual, and page 4 of the BBNEP Pocket Guide. So you won’t have to look back to it again and again, it’s also on the bottom of the BBNEP enhanced DEP data sheet.

If you see this amount of cover for a species, then record this amount:

| 1- 5% | 3.0% |

| 6- 15% | 10.5% |

| 16- 25% | 20.5% |

| 26- 50% | 38.0% |

| 51- 75% | 63.0% |

| 76- 95% | 85.5% |

| 96- 100% | 98.0% |

Once you have made all your vegetative observations follow the procedures for transforming the percent cover into percent dominance and determining dominant species that are shown in the DEP Manual. Keep a copy with you of the BBNEP Wetland Delineation Pocket Guide in case you need reminding on the procedures out in the field.

If you find it all a little confusing, there is a great DEP publication, Delineating Bordering Vegetated Wetlands in Massachusetts that was put out in 1995.

SOILS

The SOILS workshop focuses on the fourth step of the wetland identification process; confirmation of wetland hydrology. In addition to the DEP Manual, BBNEP Wetland Delineation Pocket Guide, and BBNEP Improved DEP Data Sheet You’ll need the following to get started:

The U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resource Conservation Service and University of Massachusetts got together and produced “Documenting and Describing Soil Conditions”. The BBNEP has updated this as the “Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program Pocket Guide to Describing and Documenting Soil Conditions”.

There is a good handout prepared some years ago about the chemistry of hydric (wetland) soils, Pedogenic Processes in Hydric Soils and Redoximorphic Features.

If it’s all too confusing, the problem may be that you need a little work in surface geology. “Geologic Deposits” by Peter Fletcher, and some internet searches is a good place to start.

There is also the Field Indicators of Hydric Soils, version 7 which has some nice color photos of redoximorphic features. Keep in mind that the federal criteria for hydric soils in this publication does not exactly match up with the primary DEP criteria found in the DEP Delineation manual. (Note that there is a link for the errata for this document.)

You also might want to look at the 2014 Fall BBNEP/MACC Soils Workshop presentation that has all the lecture notes included.

You will also need a shovel, a ruler, and a Munsell color chart.

Figure 5. Always start your soil investigation with digging a hole. Make the hole big enough to get a good view of the soil profile. Photo by John Rockwell at the BBNEP/MACC Advanced BVW training session.

Step 4: Confirmation of wetland hydrology – This means Soils!

Certain soil characteristics indicate wetland hydrology. Learn these characteristics to become a good delineator! Dig a test pit large enough to confirm the soil conditions. Use the information from the DEP Delineation Manual to evaluate soils. We have included links to the excellent NEsoil website.

Soils are described by Depth, Horizon, and Color.

Horizons

Soil horizons are used to describe the layers that one sees as one looks at a hole. These main layers, or Master Horizons, were first called layers A, B, and C. Simple soils are still referred to as ABC soils! Horizons are differentiated by color and texture.

The master horizons you will likely encounter are:

O – organic

A – mineral topsoil,

E – elluvial

B – mineral subsoil,

C – parent material

R – hard bedrock

Common subclasses Ap, Bw, Bhs, and Bg. A complete list of subclasses starts on page 50 of the NRCS Soil Survey Manual.

Depth

Depth is usually measured down from the top of the mineral soil surface, less the duff layer. For organic soils (soils with greater than 8 inches of organic material), the depth is measured from the top of the organic material (less the duff layer.)

| 4″ – 0″ | O |

| 0″ – 4″ | A |

| 4″ – 20″ | B |

| 20″ – | C |

This is shorthand for 4 inches of organic material over 4 inches of topsoil over 16 inches of subsoil over the parent material. Notice the measurement of depth (0″) starts at the top of the A horizon.

For an organic soil (one with over 8 inches of organic deposits) you might have something like this:

| 0″ – 12″ | O |

| 12″ – 24″ | B |

| 24″ – | C |

which is shorthand for 12 inches of organic material over 12 of subsoil over the parent material. Notice the measurement of depth (0″) starts at the top of the O horizon.

Color has been standardized by the use of the Munsell Soil Color Chart. The colors are differentiated by hue, value, and chroma.

Hue is that attribute of a color by which we distinguish red from green, blue from yellow, and so on. Each page of the Color Chart is a different hue. The redder hues are in the front, the yellower hues in the back.

Value indicates the lightness of a color. The scale of value ranges from 0 for pure black to 10 for pure white. The value increases as one goes down a page in the color chart. (Black, white, and the grays between them are called “neutral colors.” Neutral colors have no hue and can be found on the “Gley 2” chart.)

Chroma is the degree of departure of a color from the neutral color of the same value. Colors of low chroma are sometimes called “weak,” while those of high chroma are said to be “highly saturated,” “strong” or “vivid.” Imagine mixing a little vivid yellow paint with a gray paint of the same value. The chroma increases as one moves from left to right across a page of the color chart.

When denoting color characteristics from the Munsell chart, the notation may look like this:

4-10″ Bw 10YR 5/4

Translation: the subsoil between 4 and 10 inches in depth is a yellowish brown with a hue of 10YR value of 5 and chroma of 4.

Color is used to determine the presence of redoximorphic features, which can be used to determine the ground water elevation during the start of the growing season. These are considered hydric soil indicators when present within 12 inches of the soil surface.

Redoximorphic features

In addition to the background color of the soil (the matrix color) there are other color patterns present. When these colors are due to wetness, they are considered redox features. Click one of the links below to do a Google search to find useful documents on these topics.

redoximorphic features soft masses redoximorphic reddish mottles redox feature pore linings oxidized rhizospheres soils nodules and concretions iron depletions clay depletions

Texture

Sandy soils are a “difficult soil” mentioned on page 30 of the DEP Manual. “Sandy” refers to the size of the soil particle. Sandy is no longer sandy when loamy sand becomes sandy loam (sand to loam). To differentiate between sandy loam and loamy sand in the field, refer to the moist soil sample characteristics of each on page 18 of the “Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program Pocket Guide to Describing and Documenting Soil Conditions.”

Wet? Look at page 20 of the “Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program Pocket Guide to Delineating Wetlands.”,/p>

| 0-2 | A | 2.5Y | 4/1 |

| 2-7 | B | 10YR | 7/8 |

| 7-15 | C | 10YR | 7/1 |

Wet? Look at page 20 of the “Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program Pocket Guide to Delineating Wetlands.”

| 2-0 | O | ||

| 0-8 | Ap | 10YR 3/3 | |

| 8-10 | B1 | 10YR 4/2 | |

| 10-12 | B2 | 10YR 4/2 | 5YR3/4 (10%) |

Problem Areas

If problem area soils are present, contact an expert who is familiar with the “Regional Supplement to the Corps of Engineers Wetland Delineation Manual: Northcenteral and Northeast Region (version 2).” (more on this in the “ADVANCED” workshop.) In certain areas you may contact the Natural Resource Conservation Service for assistance. Common problem areas are sandy soils and evergreen forest soils (spodosols). Less common regionally are red soils from the Connecticut River valley and black soils from the southeastern area of Bristol County. Learn how to identify spodosols.

Figure 6. Attendees of the 2009 Advanced session check colors for a partially cemented spodic horizon.

Other useful Hydric Soil links:

Field Indicators to Hydric Soils of the United States V.7

National Wetland Inventory, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

NE Interstate Water Pollution Control Commission

Wetland Publications – searchable USACOE document web site

PLANTS National Database

Society of Wetland Scientists

WETs Climate Tables (growing season info)

1987 Wetland Delineation Manual (USACOE)

Regional Supplement to the Corps of Engineers Wetland Delineation Manual: Northcentral and Northeast Region (version 2)

ADVANCED – vegetation

The ADVANCED workshops focus on a more in depth look at delineation for the tough sites. on the fourth step of the wetland identification process; confirmation of wetland hydrology.

Review the “Alternative Community Analysis Techniques” section of the BBNEP Pocket Guide to Delineating Wetlands.

DEP allows the use of alternative analysis techniques provided an explanation is provided as to why it was used.

To guard against a “false negative” always use the vegetative analysis method that provides the highest vegetative line. Don’t worry about a “false positive” using vegetation, as you should be using soil information to adjust the vegetative line downward. If you receive a data sheet using an alternative method, request a DEP Dominance Test data sheet with the same vegetative information to make sure you are not being duped.

You’ll need the following to try these methods out:

Prevalence Index Data Sheet

Point Intercept Tally Sheet (from Tiner)

Vegetation Analysis Data Form – Sampling Grid for Herb Stratum (from Tiner)

Vegetation Analysis Field Data Form -Tree Stratum-Basal Area (from Tiner)

Regional Supplement to the Corps of Engineers Wetland Delineation Manual: Northcentral and Northeast Region (version 2)

Using Relative Dominance of Wetland Species by Layers to Delineate Wetlands in Massachusetts

One of the problems with strictly adhering to one vegetative technique is that, depending on site peculiarities, any one method can give a “false negative” for the vegetative criteria.

It is acceptable to use alternative delineation techniques when the Dominance Test gives skewed results. One alternative method determines the percent wetland plant community composition by the relative dominance of wetland species by layers (RDL). The RDL method was refined by Dr. Gary Sanford and was built upon vegetation mapping practices that had been in use since the turn of the century. The technique corresponds to the regulatory requirements and has been accepted at adjudicatory hearings. When using the RDL test, provide a written explanation to the Conservation Commission of how and why it was used.

Using the Wetland Site Index to Delineate Wetlands in Massachusetts

To determine the edge of the wetland, one technique to evaluate the vegetational community that has been accepted at adjudicatory hearings is the weighing method known as the Wetland Site Index (WSI). While the WSI technique does not strictly meet the requirements of the regulations for evaluating the vegetational community, there are times when its use will give an appropriately positive result for the vegetational criteria when other quantitative techniques will not.

The use of hydrological indicators should always be used when relying on the WSI for establishing a BVW boundary when the WSI is below .67. Dr. Michener, the creator of the WSI, cautioned against the strict use of the .50 value for the wetland determination cutoff point. Since the regulations include all FAC species as wetland plants, perform soil investigations when the WSI is as low as .45.

If you are using WSI data sheets, check to make sure that you are using the method that will provide the “highest line” and you have checked the soil characteristics when the WSI index is between .45 and.67.

Using the Prevalence Index to Delineate Wetlands in Massachusetts

The Prevalence Index (PI) is a simplified copy of the WSI and has been accepted at an Adjudicatory Hearing. The PI is a weighted-average wetland indicator status of all plant species in the sampling plot. All plants are given a numeric value based on indicator status (OBL = 1, FACW = 2, FAC = 3, FACU = 4, and UPL = 5) and their abundance (absolute percent cover) is used to calculate the PI.

It is particularly useful in (1) communities with only one or two dominants, (2) highly diverse communities where many species may be present at roughly equal coverage, and (3) cases where strata differ greatly in total plant cover (e.g., total herb cover is 80 percent, but sapling/shrub cover is only 10 percent). The following procedure is used to calculate a plot-based prevalence index.

At least 80 percent of the total vegetation cover on the plot must be of species that have been correctly identified and have an assigned indicator status (including UPL).

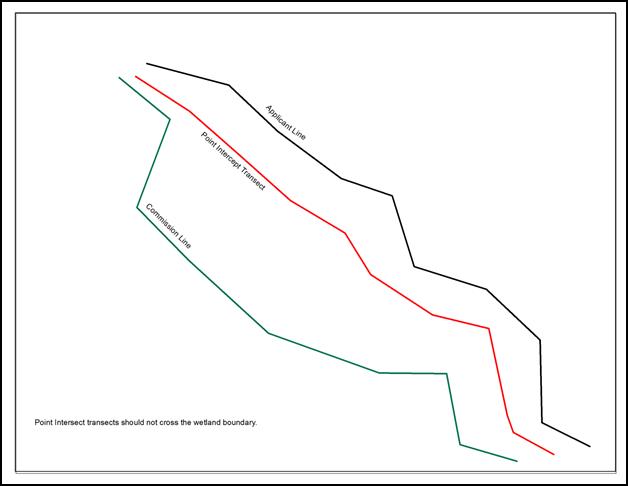

Using the Point-Intercept Sampling Procedure to Delineate Wetlands in Massachusetts

The Point Intercept Procedure is a data collection alternative to the aerial cover plots. The data collected may be analyzed using the Dominance Test, WSI, RDL, or PI procedures explained above, although Point-Intercept sampling is generally used with a transect-based PI to determine whether vegetation is hydrophytic.

The following procedure for point-intercept sampling is an alternative to plot-based sampling methods to estimate the abundance of plant species in a community. Advantages of point-intercept sampling include better quantification of plant species abundance and reduced bias compared with visual estimates of cover. The method is useful in communities with high species diversity, and in areas where vegetation is patchy or heterogeneous, making it difficult to identify representative locations for plot sampling. Disadvantages include the increased time required for sampling and the need for vegetation units large enough to permit the establishment of one or more transect lines within them. The approach also assumes that soil and hydrologic conditions are uniform across the area where transects are located. In particular, transects should not cross the wetland boundary.

In point-intercept sampling, plant occurrence is determined at points located at fixed intervals along one or more transects established in random locations within the plant community or vegetation unit. If a transect is being used to sample the vegetation near a wetland boundary, the transect should be placed parallel to the boundary and should not cross either the wetland boundary or into other communities. Transect length depends upon the size and complexity of the plant community and may range from 100 to 300 ft or more. Plant occurrence data are collected at fixed intervals along the line, for example every step (about 3 feet). At each interval, a “hit” on a species is recorded if a vertical line at that point would intercept the stem or foliage of that species. Only one “hit” is recorded for a species at a point even if the same species would be intercepted more than once at that point. Vertical intercepts can be determined using a long pin or rod protruding into and through the various vegetation layers, a sighting device (e.g., for the canopy), or an imaginary vertical line. The total number of “hits” for each species along the transect is then determined. The result is a list of species and their frequencies of occurrence along the line. Species are then categorized by wetland indicator status, the total number of hits determined within each category, and the data used to calculate a transect based result. The formula is similar to that used for aerial cover estimate for whatever method is used, except that frequencies are used in place of cover estimates.

When you are unable to come to an agreement regarding the cover estimate for any particular vegetative strata, use data collection methods that are less likely to involve observational errors.

For the ground cover, consider using a sampling grid. Its relatively easy to use and they can be made by anyone who is just a little handy. The shrub layer can be documented by measuring each shrub or group of shrubs with a tape measure and the tree layer can be evaluated by measuring the basal area of each tree then totaling the basal area for each species.

Figure 7. Example of appropriate application of the Point-Intercept method.

ADVANCED – Soils

The list of Hydric soils in the DEP manual is not a complete list (the DEP manual categorizes them as “a list of some hydric soil indicators”).

In fact, there is no complete list and research is ongoing to refine and add to existing hydric soil descriptions. We are lucky to have an active society for soil scientists and several research institutions in New England, so the list of hydric soils is continually evolving.

For delineating bordering vegetated wetlands under the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act, you should be drawing on the hydric soil criteria in the DEP Delineation Manual, Field Indicators for Identifying Hydric Soils in New England (version 3), and the Regional Supplement to the Corps of Engineers Wetland Delineation Manual: Northcentral and Northeast Region (version 2).

We have combined the information from these sources and placed it in one document, the Pocket Guide to Hydric Soils for Wetland Delineation in Massachusetts (version 2.1).

Figure 8. Attendees of the 2013 Advanced session using a sampling grid.

DELINEATION TIPS

1. Get the proper attitude – remember, it’s all about the hydrology.

2. Study area: The area of interest is rarely the 30-foot radius of the DEP guide. The study area should give you information that you can use in determining the edge of the wetland. On either side of a wetland flag! You have to modify the study area size to answer the question you are trying to ask. If you have a 15 foot difference between Delineator A and Delineator B, then the study area should be that 215 foot strip.

3. Plants with morphological adaptations to wetland conditions are wetland plants. The most commonly seen attribute is shallow root systems. Southeast Massachusetts is well known for the white pine (Pinus strobus) and pitch pine (Pinus rigida) wetlands. In coastal areas, these can usually be identified by blowdowns from Hurricane Bob (1990).

Figure 9. Blowdown due to shallow root system. This is a common adaptation of white pine, Pinus strobus, to wet conditions. The white pines in this area would be considered wetland plants due to the shallow root systems.

4. Hydrology information from soil characteristics should be the primary delineation tool in wet meadows where plants are unidentifiable due to cropping (see page 48 of the DEP manual). [Studies have shown that the wetlands rating of the dominant species, that are visible, change from FACW to FACU over the course of the growing season.] NOTE: The draining of farm fields, using drain tiles or drainage ditches, will not change soil characteristics. This may result in a false positive indicating wetlands. However, there are many instances where the lowering of the water table in a farm field will allow farming but still allow for hydric conditions. The growing season starts in April, but the fields many times don’t dry out until June. That leaves more than enough time to develop anaerobic conditions, and still get a crop in.

5. Problem Soil #1 Spodosols referred to as “evergreen forest soils” on page 31 of the DEP Manual and page 21-22 of the BBNEP Pocket Guide.

Figure 10. These soils are quite varied but were all found within 100 feet of each other at Washburn Park in Marion. The three on the right are samples from a disturbed site. The left sample is a wet spodosol. Photo by John Rockwell

A spodosol can be identified in undisturbed areas by an eluvial layer above the spodic horizon. (See the Wikipedia page, for a nice European spodosol and description of the formation process.) For field ID of spodosols use the criteria in the definition section of “Field Indicators for Identifying Hydric Soils in New England, version 3.”

Note: There are more hydric soils than there are in the DEP Manual. Use the Pocket Guide to Hydric Soils Wetland Delineation in Massachusetts (version 2.1) for the more complicated sites that are not in the DEP manual.

Figure 11. Soil sample with redox features found in a spodic horizon by the 2009 Advanced trainees.

Web Resources for hydric soil identification

NRCS Web Soil Survey http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/WebSoilSurvey.aspx has all the soil information you need to file a report.

Delineation Assistance on the Web:

2012 USACOE Delineation Manual Regional Supplement to the Corps of Engineers Wetland Delineation Manual: Northcentral and Northeast Region (version 2)

Test your ability to differentiate colors. Use a self-test to check your ability to distinguish color variation. Check out https://www.xrite.com/hue-test. 1 out of 255 women and 1 out of 12 men have some form of color vision deficiency.

Basic Stuff

A. DEP Forms: All the DEP Wetland Application forms in both Word format and as a pdf. For the most current forms always check the DEP website www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/massdep/water/watersheds/wetlands-protection.html#forms

B. DEP Program Policies and Links (including Maps of Coastal Rivers), can be found at https://www.mass.gov/lists/water-resources-policies-guidance

C. When recording your data, the DEP data sheet found in Appendix G of the DEP manual is good but the BBNEP Improved DEP Data Sheet is better.

Advanced Materials

A. Existing Vegetation and Classification Mapping Technical Guide.

B. Field Book for Describing and Sampling Soils, Version 3 .

C. Soil Drainage Classification and Hydric Soil Indicators has a nice discussion of hydric soil chemistry.

D. Introduction to Field Indicators for Identifying Hydric Soils in New England, Version 3. Good pdf version of PowerPoint Presentation made to the SNESS from the www.nesoil.com website.

E. The Association of Massachusetts Wetland Scientists’ link to “List of Selected Wetland Publications”.

F. Army Corps Wetland Delineation Manual, 1987.

H. Identifying Problem Hydric Soils.

I. A Guide to Hydric Soils in the Mid-Atlantic Region.

J. Hydric Soil Overview PPT Presentation. Download this presentation and you will be able to view the notes pages.

K. Redoximorphic features PPT Presentation. Download this presentation and you will be able to view the notes pages.

L. Soil Formation PPT Show at www.nesoil.com.

M. Soil Horizon PPT Show at www.nesoil.com.

N. Soil Texture PPT Show at www.nesoil.com.

O. Soil Color PPT Show at www.nesoil.com.

P. Northeast Wetland Flora, Field Office Guide to Plant Species.

Q. The PLANTS database has links to a key for pines, spruces, etc., “Key to Gymnosperm Species of the United States”(gymnosperms.zip), “Key to Grasses of Massachusetts”(massachusetts_grasses.zip), and “Key to Wetland Monocots”(wetland_monocots.zip). These can also be used on the interactive site.

R. The Association of Massachusetts Wetland Scientists’ link to “Must have” Books in Your Wetland Library

Visit: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/conservation-basics/natural-resource-concerns/soil/soil-use for more information about hydric soils.

The Pocket Guides by the Buzzards Bay NEP and others

Print these booklet versions of the pocket guides on 8.5 x 11-inch paper on a double-sided printer to create your own booklets.

Pocket Guide Wetlands Delineation 2021 update (printable booklet format page ordering)

Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program Pocket Guide to Describing and Documenting Soil Conditions (booklet).

Field Indicators for Identifying Hydric Soils in New England” version 3 (booklet).

Supplement to Field Indicators for Identifying Hydric Soils in New England” version 3 (booklet).

Pocket Guide to Hydric Soils for Wetland Delineation in Massachusetts (version 3.1) (booklet-use glossy paper).

E book versions

The ebooks are pdfs that with sequential pages. They may be read on a tablet or printed. If printing, the original page size is 5.5″x8.5″.

Pocket Guide Wetlands Delineation 2021 update (ebook)

Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program Pocket Guide to Documenting and Describing Soil Conditions (ebook).

Pocket Guide to Hydric Soils for Wetland Delineations in Massachusetts 2019v4_1_booklet (ebook).

Field Indicators for Identifying Hydric Soils in New England” version 3 (ebook).

Supplement to Field Indicators for Identifying Hydric Soils in New England” version 3 (ebook).

Continuing Education:

Wetland delineation course from Ralph Tiner. Check out The Institute for Wetland & Environmental Education Research.

Soil Morphology and Mapping with Peter Fletcher.

DEP Adjudicatory Hearings

DEP Adjudicatory Hearing Decision Index, 2011-2014 (a pdf file useful for searches).

DEP Adjudicatory Hearing Decisions Online (decisions listed by year).

Free Search at Landlaw.com (1994 to present).